Malta is a unique Mediterranean island nation, distinguished by its own language, a strong entrepreneurial culture, and its proud membership in the European Union. It comes as no surprise that around 75% of Maltese businesses are family-owned, forming the backbone of our economy.

Larger corporations and regulated industries, such as financial services, insurance, and banking, operate under strict EU directives, MFSA supervision, and other regulatory frameworks. Their governance and reporting structures are closely aligned with European standards, ensuring transparency, consistency, and accountability.

By contrast, many family businesses in Malta tend to operate with far less formality. Decisions often blend business logic with personal dynamics, and governance structures can become entangled with family relationships. What should be a straightforward process can quickly turn into a complex puzzle, influenced as much by tradition and emotion as by strategy and regulation.

Imagine two roads: one is straight, well-marked, and regulated...the path followed by Malta’s listed and EU-regulated companies. The other is winding, less predictable, and shaped by tradition.... the journey of Malta’s family businesses. Both roads move forward, but the second requires more attentive navigation, built on trust, communication, and sound professional guidance.

In many ways, it mirrors the difference between leading a big country with formal systems and leading a close-knit island, where ties of kinship and familiarity shape every decision.

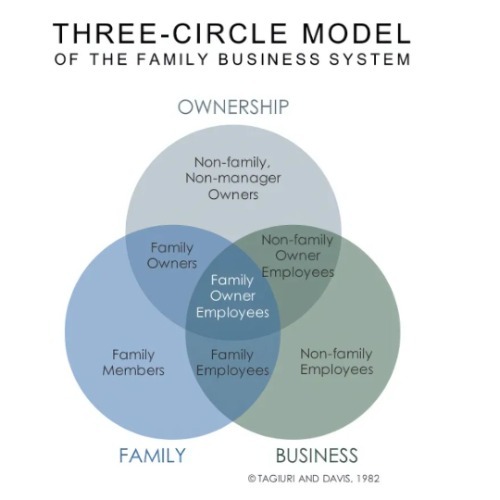

How Three Circles Changed the Way We Understand Family Business

The Three-Circle Model of the Family Business System, created by Renato Tagiuri and John Davis at Harvard Business School, is highlighted as a widely used framework for understanding family businesses. This model illustrates the interaction between three overlapping subsystems: Family, Ownership, and Business. Individuals in a family business may belong to one, two, or all three circles, and the overlapping roles often explain both the strengths and the conflicts within family enterprises.

At the heart of the complexity is the overlap between family and business roles. Family members often tie their identity to the company, so choosing one path over another—or considering an external leader—can feel like a personal rejection. This dynamic may give rise to tension, sibling rivalry, or concerns about preserving the family legacy.

The mindset is also distinct. In family businesses, owners frequently take on multiple responsibilities. This multifunctional environment allows individuals to develop a broad skill set and gain hands-on experience more quickly than in larger organisations, where roles are often more narrowly defined.

Generational Challenges and Governance Gaps

Each generation faces different hurdles in succession:

First generation (founders) often struggle to let go, equating the business’s success with their own identity.

Second generation can grapple with power-sharing conflicts among siblings and alignment on strategic direction.

Third generation and beyond often introduce governance gridlock, as multiple stakeholders with different agendas complicate decision-making.

Without clear governance, such as family charters, or formal decision-making bodies, succession plans can stall or fail.

The Cost of Delay — The Urgency of Planning

Succession is one of the most complicated transitions a family business will face, and starting early is vital. Without early planning, businesses may face problems—from enthusiastic but unprepared successors to sudden founder incapacity or death.

Values, Expectations, and Family Philosophy

Clarifying family philosophy and values is a key first step. Families must ask:

Will unity trump wealth?

Will meritocracy drive decisions?

How will equality between branches or siblings be managed?

These guiding principles shape fair criteria for leadership succession.

Objective Assessment and Development of Successors

Candidates — whether family members or not — should be assessed on merit, readiness, and leadership potential. Many businesses fall into the trap of assuming that birth order equals competence.

Instead, families should invest in development:

Self-awareness

Adaptability

Relational skills

This preparation often begins one to two years before a transition and ideally includes coaching and mentoring.

External Advisors, Objectivity, and Integration

When family members lack readiness, impartiality matters. External advisors play a critical role—defining criteria, managing expectations, and facilitating searches fairly.

Bringing in an external leader doesn’t diminish family influence if properly managed. Governance structures—family councils, charters—can help external executives align with core values and ensure smooth cultural integration.

The Role of AIMS International in Succession Planning

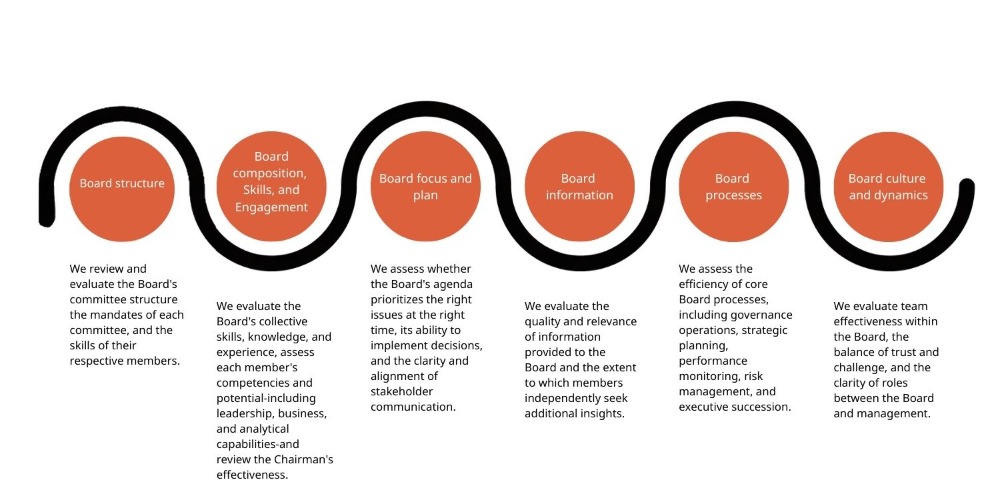

Boards are increasingly recognising that effective succession planning requires both internal leadership development and external market mapping. At AIMS International Malta, we can offer our advisory role in helping you shape your succession planning strategy.

Our advisory services include:

Conduct board evaluations

Provide board member assessments

Design succession planning frameworks

Offer coaching for boards

Identify and shape visionary leaders

Our expertise spans from Executive Search (which is more than a recruiter), Leadership Development, Talent Management, Board Services and Family Business advising - a comprehensive suite designed to cultivate leaders who transform and inspire with a focus on responsilble leadership and impact. As your governance partner, we support your Board in fulfilling one of its most vital duties: ensuring your business is never without strong and capable leadership.

We help you navigate the winding path of family business succession with careful attention, providing guidance grounded in trust, clear communication, and professional expertise.

Formalising Succession via Governance Mechanisms

Family charters and advisory boards can reduce ambiguity and foster accountability. While not legally binding, they clarify roles, responsibilities, and conflict-resolution steps. They also empower family members outside of executive positions to contribute meaningfully, for example through board governance functions.

Practical Guidance: Early, Inclusive, Structured, and Compassionate

Begin early and involve all generations — even those not currently in the business.

Define clear criteria for leadership — based on competencies, values, and vision.

Implement phased transitions — shadowing, partial operational leadership, then full succession.

Use governance tools like family charters.

Consider external leadership with care, ensuring cultural fit and smooth onboarding.

Promote cross-generational learning, encouraging successors to gain outside experience.

Summary

Succession planning in family businesses straddles both business and emotional dimensions. Effective strategies include early preparation, shared values, strong corporate governance, clear decision-making frameworks, fair assessments, and the strategic use of executive search partners.

By balancing legacy with innovation, family businesses can protect their heritage while ensuring resilience for future generations. With each new chapter in the business comes the need for movement in the C-suite.

👉In a subsequent article, we will explore this topic in greater depth, examining practical strategies for leadership transitions and board evolution.

“Little do we realise that when we start with a simple idea and a goal — forming a business and building a legacy — we are also unknowingly stepping into a journey that requires us to think long beyond ourselves. One day, the question will not be just how we grow, but how we let go.” — Louise Vella, Managing Partner @ AIMS International Malta

This article is part of a six-part series on Succession Planning, created to help family businesses plan confidently for leadership transitions. Look out for the next piece in the series.

Sources and Further Reading

Cesaroni, F. M., & Sentuti, A. (2017). Family business succession and external advisors: The relevance of “soft” issues. Small Enterprise Research, 24(4), 366–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2017.1398897

Davis, J. A., & Tagiuri, R. (1982). Bivalent attributes of the family firm. Working Paper, Harvard Business School. (Reprinted 1996, Family Business Review, 9(2), 199–208).

Davis, J. A. (2018). Governing the family-run business. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. Retrieved from https://www.library.hbs.edu/working-knowledge/governing-the-family-run-business

Trujillo, M. A. (2021). Advisors in corporate governance of family firms. Journal of Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 1–20. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/205/20574633003/html

Abraham, M., Lourenço, A., & Pereira, J. (2020). Succession planning and strategies in family business: A multiple case study. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 19(6), 1–17. Retrieved from https://www.abacademies.org/articles/succession-planning-and-strategies-in-family-business-a-multiple-case-study-10323.html

Tribolet, H., & Wielsma, A. J. (2025). Stabilising a family business: The transformation of governance mechanisms in times of change. Journal of Management History, 31(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2025.2461029

About the Author

Louise is a seasoned professional with over 25 years of experience in the Corporate Services Provider (CSP) industry. She has supported a wide spectrum of clients—including those from the corporate, private, and public sectors, as well as entrepreneurs—across various aspects of company secretarial work, corporate governance, trustee, directorship services and risk management.

How Can I Help You Preserve Your Family Legacy?

Unlike larger corporations that adhere to clearly defined pathways guided by EU directives and governance frameworks, family businesses often navigate intricate routes shaped by tradition, emotional considerations, and close personal relationships. Consequently, succession planning represents one of the most formidable challenges that any family business will encounter.

I'm happy to share insights and provide you with a solution that meets the specific needs of your family business.